/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/59667069/01.0.png)

Last summer, OCAD University student Ryan Mason spent much of his school holiday huddled in front of a television digitizing his parents’ old home movies. He purchased a new VCR and capture card just for the occasion, but the process took longer than he anticipated: he had to actually watch through each tape, from beginning to end, in order to make digital versions. It was a process awash in memories, and for the rest of the summer the 28-year-old design student couldn’t stop thinking about VHS tapes.

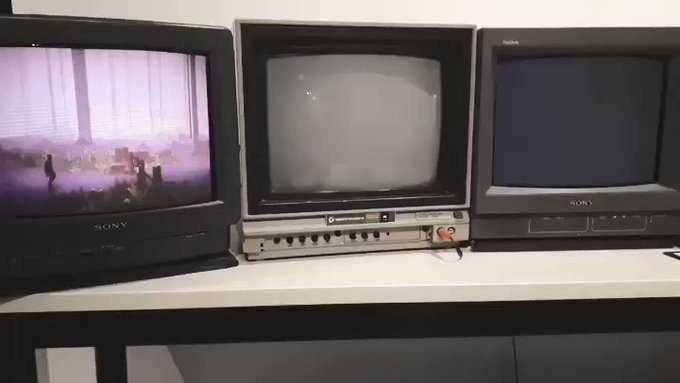

When he returned to school in September and started brainstorming his thesis project, those thoughts on defunct technology turned into a plan: he was going to design a VHS-based video game console that could have existed in the early 1980s, if it weren’t for that pesky video game crash in 1983. Last week at OCAD University’s annual student showcase in downtown Toronto, Mason showed off a fleshed out version of his idea that allowed participants to play one of three different games across 10 old-school tube TVs simultaneously, the image bouncing from set to set. It was like a piece of game history from an alternate timeline.

He even dreamed up an elaborate backstory for the company and hardware (the fictional console is called the Cathode MK.1) and envisioned a form of digital distribution that could’ve been revolutionary at the time. Instead of going out and buying new games on tape, he imagined players would be able to record game data from a special TV channel onto a cassette and then play it on their console. Mason describes this design process as “going back in and bringing some of that lost potential [of the 1980s] to the future.”To further flesh-out this alternate future, he developed three game prototypes. One is a simple 3D adventure game with a meta-textual twist: you’re exploring the home of the fictional game console company’s founder, who went on to become a recluse decades after it launched. The multi-screen setup — which in this instance involved two rows of five TVs stacked on top of each other — really gives a sense of place. Each TV represented a room, and so as I transitioned from one to the next, it gave a feeling of moving through a physical location. I had to actually switch seats in order to read all of the text on different screens.

The other two games were much more arcade-oriented. One was a co-operative experience in which you had to move a wobbly cube through a series of puzzles; one person controls the cube, while the other has to move bridges and platforms to help the blocky hero along. The other game was much more familiar: Pong. What made this version particularly unique was that the play area was spread across all 10 TVs; the screens would follow the path of the ball, lighting up as it bounced around, while all the others remained dark or displayed static. This meant that players had to predict the trajectory of the ball, as well as keep track of where exactly their paddle was when the screen flicked off.

For Mason, the project was a chance to explore technologies like VHS and multi-screen play that went underutilized in games because of the industry crash. While the games don’t actually run off of VHS tapes in this incarnation, it looks like they do; beside the displays is a VHS deck, and when you insert a cassette the machine reads the game information off of an IR sticker. So you still swap games by changing tapes, even if the act is mostly performative.

The TVs for his project came from a variety of places — some were property of the university, while others were donated or bought for cheap off of Craigslist — and Mason estimates he spent about $30 putting together the rest of the setup. That includes an Arduino Uno to power it, and a switch that allows the game’s image to move from one TV to the next. According to Mason, the screen-swapping that’s so integral to the experience was fairly easy to set up. “I’m moving a camera in the game engine, and switching the output at the same time,” he says. “It gives you the illusion that there’s something more magical happening, but it’s actually very simple.”

It’s also just one permutation of the idea. Each game is built to work with any number of screens. (In fact, you can download a free, single-screen prototype for the adventure game That Night right now.) And for multi-display setups, the TVs don’t even have to be side by side; Mason envisions an escape room experience with televisions scattered around a room, where players have to follow a sound or visual to solve puzzles. But he’s also looking to create some more classic arcade-style experiences. When he’s shown off the project to the public, he’s found that the retro nature of the hardware makes it very approachable and conducive to games like Pong. “When people interact with this, it’s kind of like they’re interacting with junk,” Mason explains. “So it becomes a lot more playful.”

While the creator admits that his project doesn’t have much of a future as a commercial product, the response from the public has been strong. A video of multi-screen Pong running across three old tube TVs received more than 25,000 likes on Twitter, and since then a number of developers have reached out to Mason about creating games for the platform. He’s hoping to eventually launch a kind of global game jam to generate new experiences, which will include making the software freely available so anyone can build their own Cathode MK.1. For now, he’s focused on exploring just what kind of game works best on a strange, retrofuturistic console like this. “I’m still not sure,” says Mason.